The geography and the landscape of the Adirondacks have always formed a sort of “border of challenges." Let’s face it: living here isn't always easy. The winters can be long. The roads are few. The landscape can be unbelievably stubborn. Therefore, the people that settled here are, most definitely, one of a kind. You have to be willing to let the wildness of the land itself form you; be open to paths that the forests within the Blue Line open to you. If you try and force something on the wilderness around you, chances are, the land will win. Don’t bet against the land of the Adirondacks.

So it should not be a huge surprise that year-round settlers of the Park, didn’t appear until about 200 years ago. Prior to the early 1800s the Adirondacks were used by the Algonquin and Iroquois as a hunting ground and for traveling “through-routes.” Even they weren’t crazy enough to try and settle here. But around 1800, rich iron deposits were discovered, timber operations flourished and hard-working people, intent on carving out their own little niche in the frontier wilderness of the Adirondacks, began to trickle into the area. These newcomers had to be resourceful and so it was only natural that those who were going to survive here became adept at hunting and fishing. Because getting venison, bear, or any other Adirondack game meat on the table was a necessary means of survival, there was little discrimination in developing tracking, shooting, trapping, and fishing skills. Men and women both became accomplished at living off the land.

Around the turn of the 19th century, people living in America’s cities had new found wealth, an eagerness to explore new territories and the time to do it. The Adirondacks became the “go to” place for people wanting to escape the heat and confines of urban life. Of course, once they got here, these “green” visitors needed some help navigating the terrain and exploring the forests of the Adirondacks.

Enter: The Adirondack Guide.

Loggers and other Adirondack settlers found they could make some good money escorting these city folk or “sports” around in the woods; taking them hunting, fishing, and, in general, making sure they had a “true” Adirondack wilderness experience. Most of these guides were men. But, a small number were women. One of these women was Julia Adella Burton Preston—one of the first licensed female Adirondack Guides.

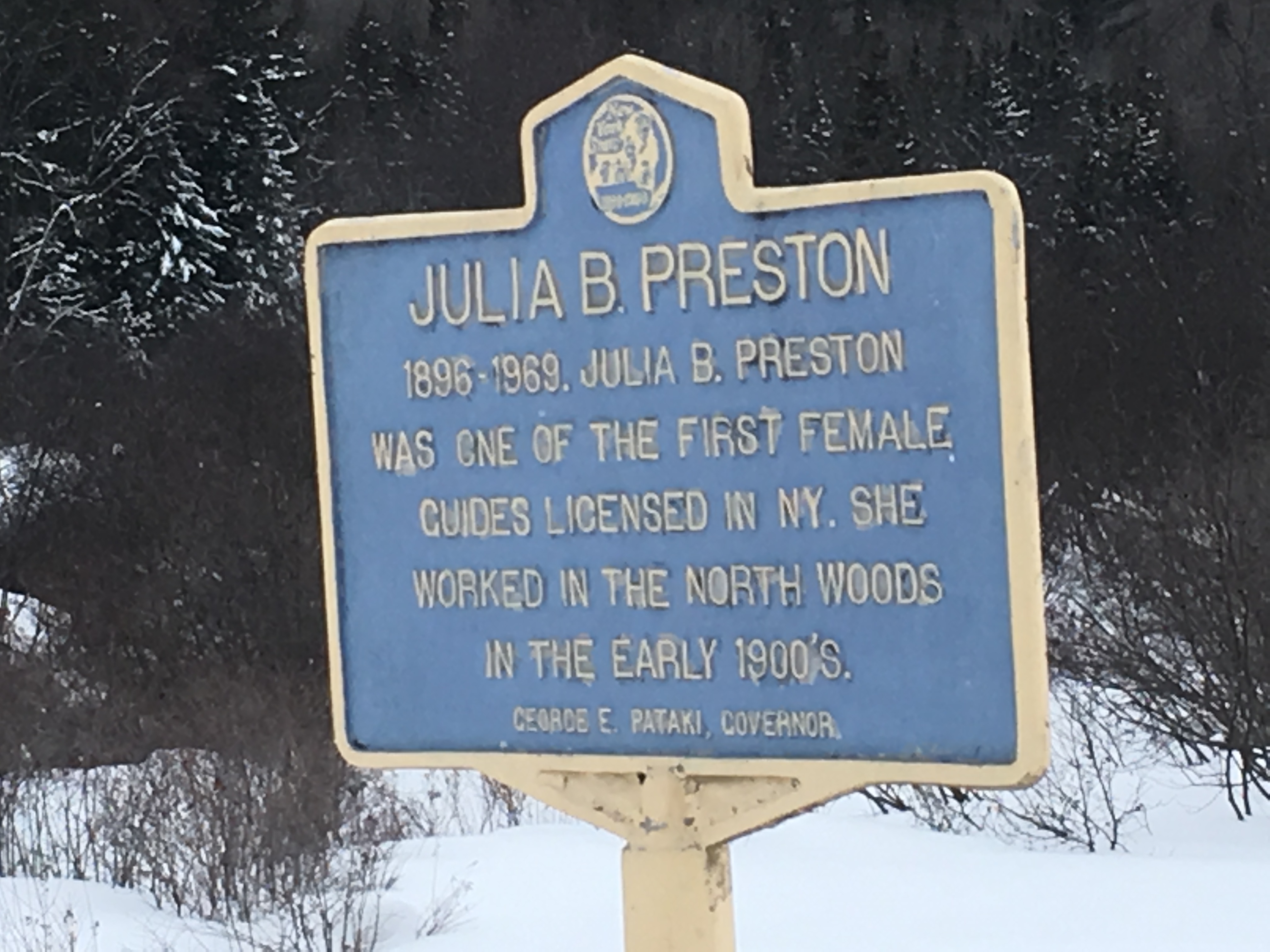

On a recent ride out to Piseco for a hiking trip, I passed a sign honoring Julia B. Preston, one of the first female NYS guides. The sign was right next to a traditional log house and I was intrigued. I set out to see what I could find out about Julia.

I tracked down her granddaughter, Kathy Hawkins, who still lives in the log house (well, truth be told, she splits her time between the log house and a newer house about a hundred yards away). Kathy was nice enough to spend some time talking to me about her grandmother and even invited me to the house to check out some old family photos.

The Courtneys, Julia’s mother’s family, were some of the very first early settlers to the Lake Pleasant area. Julia’s father, John Burton, was an orphan from Canada. As a young boy, he was adopted by a Quebecois trapper. They traveled together down to Boston and eventually made their way over to the Adirondacks. In Piseco, John Burton met and married Annie Courtney. They proceeded to raise a family and eke out a living in the Adirondack Mountains.

In addition to working a small farm and trapping, John also worked as an Adirondack Guide. John’s adoptive father, the trapper, had taught John well and, in turn, John shared his acquired trapping and hunting skills with his own children. (Only three survived passed infancy; Julia’s twin older brothers died of whooping cough at about one month old.)

Life in the Adirondack mountains in the early 1900s meant there was always a “gun by the back door.” You never knew when you would need it for protection, hunting, or to rid your garden of any four-legged thieves. So Julia, born in 1896, learned how to shoot alongside her younger brothers, Richard and Raymond. At a very early age she became an excellent shot. She often told people that she shot at least one buck a year her entire life. That is, until she sawed off the tip of her trigger finger — but that’s another story.

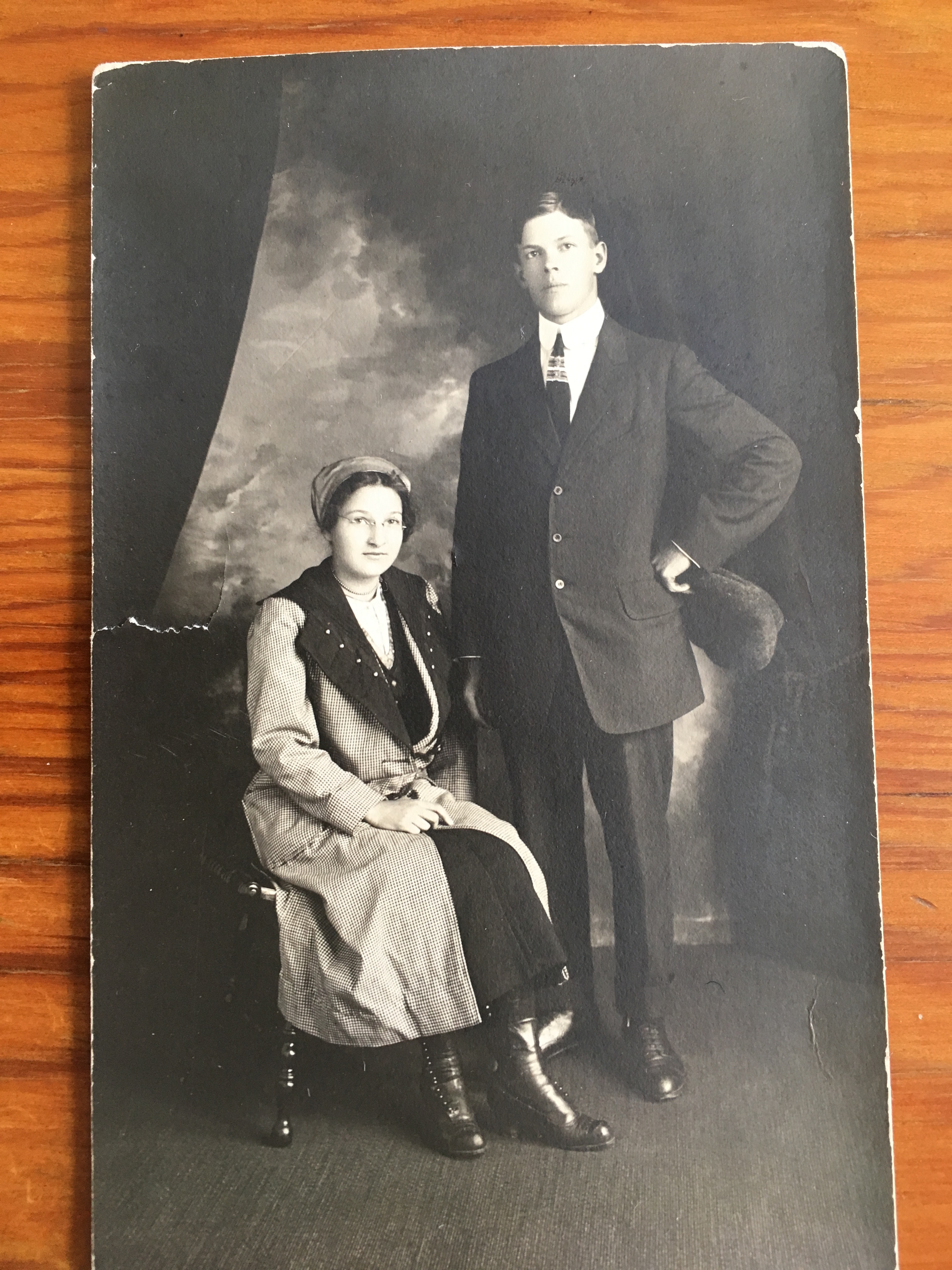

Julia most likely started guiding alongside her father when she was in her early teens. Then, when she was in her mid-teens, Julia met Charlie Preston. Charlie’s father owned hotels in Wells and Northville. Charlie himself drove the stagecoach between Northville and Lake Pleasant - and, of course, he was an Adirondack Guide.

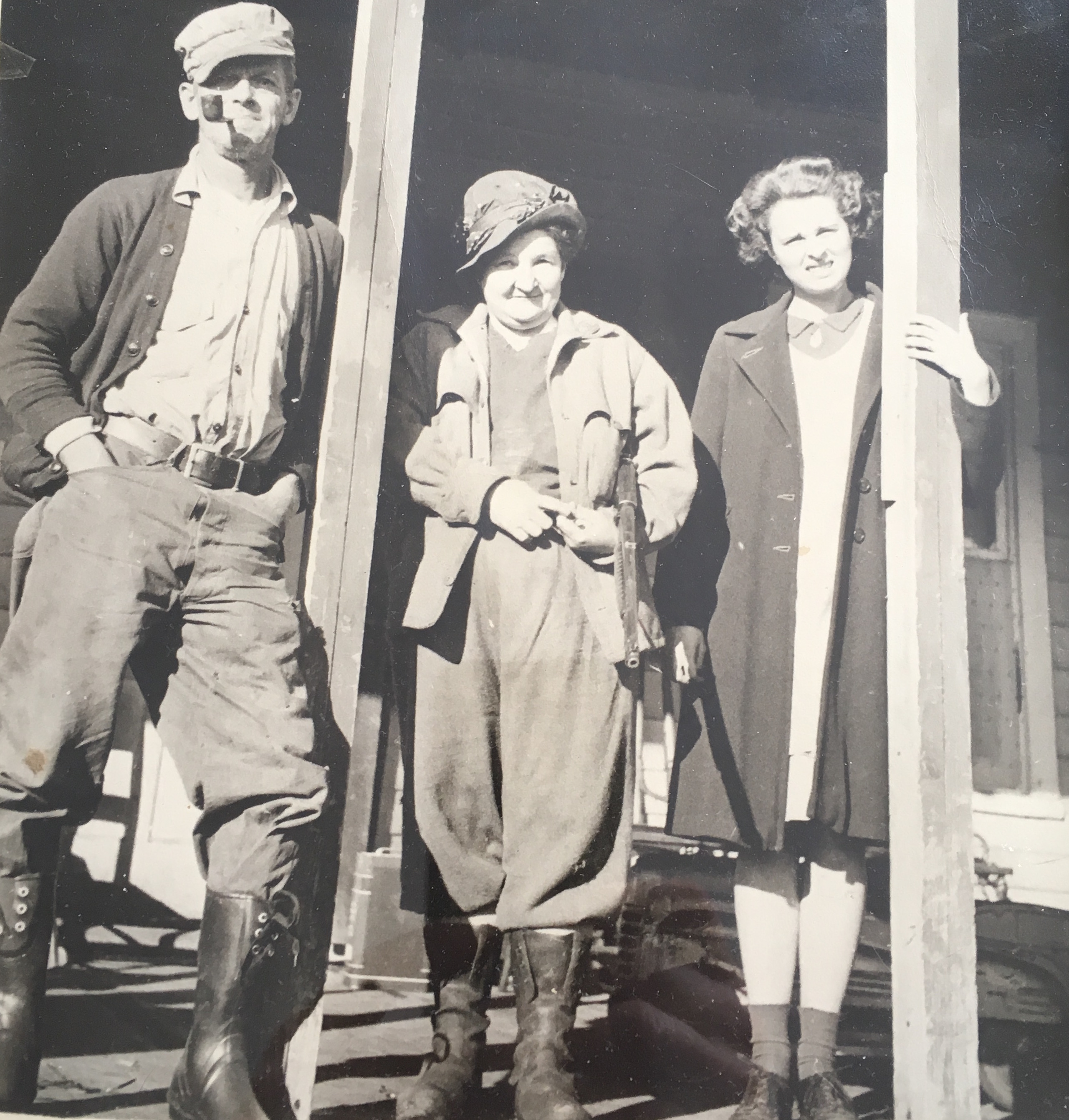

Charlie and Julia were married when Julia was just sixteen, and naturally the two began taking “sports” out together on guided hunting trips. This was the early 1900s in the Adirondacks. It wasn’t really feminism that encouraged Julia’s guiding work, but more of the reality of the day. Guiding was a way to earn some good money from out-of-towners. As Charlie would say, “We were both equal. We both did the same work.” Some hunters would balk at having a woman accompany them on their manly hunting expeditions, but Charlie would simply say, “Too bad.” Julia was his partner.

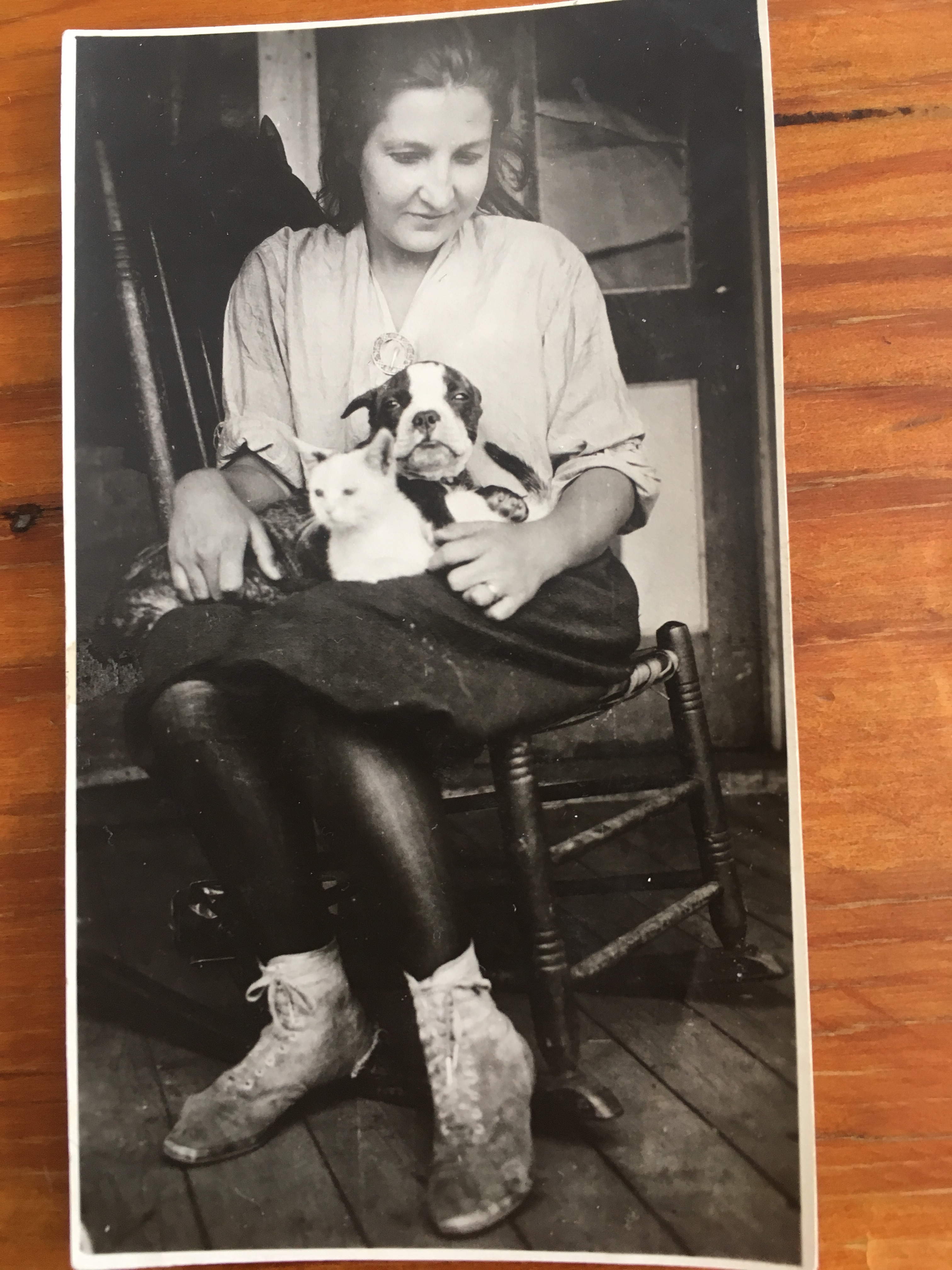

Both Julia and Charlie were very fond of animals and were known to take in some of the orphaned ones they found. There was a baby hawk, a three legged fox, a mink, even a black bear… Julia even fed the bear with a baby bottle.

Julia and Charlie had three children - John, Homer and Betty - before Julia turned 23. In 1943, the family homestead in Piseco burned to the ground. World War II was being fought and Charlie was away in the US Navy, a member of the Seabees. So while he was gone, Julia worked with her brother Richard and her Uncle Tom to build the log cabin where the plaque honoring her currently stands — and where her granddaughter, Kathy, still lives.

The New York State Guide Program didn’t start until 1914 and the records on when Julia became an official guide have been lost. But sometime in the 1920s, Julia became one of the first women—if not THE first—to be a licensed Adirondack Guide.

There's plenty of history to be explored here in the heart of the Adirondacks. But there's no need to rough it like the first explorers (unless you want to!). Why not plan to settle in for a few days and explore the modern way — we have guides to help lead the way, restaurants serving up local cuisine, and warm places to rest your head.

There's plenty of history to be explored here in the heart of the Adirondacks. But there's no need to rough it like the first explorers (unless you want to!). Why not plan to settle in for a few days and explore the modern way — we have guides to help lead the way, restaurants serving up local cuisine, and warm places to rest your head.